By Virigil Elliott

Painters interested in Old Master effects benefit from a good understanding of the differences between modern tube oil paints and the paints used by the Old Masters whose works they admire. Too often this important issue is overlooked, and the focus tends to be disproportionately on mediums and additives, while the paints themselves generally receive too little attention. There are significant differences to be acknowledged between modern paints and the oil paints in use in the 17th century and earlier.

Saint Luke Painting the Virgin by Niklaus Manuel Deutsch, 1515

The Old Masters' paints did not contain aluminum stearate or beeswax as stabilizers, which additives alter the brushing qualities of oil paints and make them "shorter," as we see in modern-day tubed oil colors. Linseed oil as a binder, without stabilizers, makes for "longer" paint, i.e., one that flows in the direction of the brushstroke rather than in all directions. Enamel is an example of an extremely long paint. Of course, the Old Masters also had walnut oil to mull their paints in, and walnut oil makes a somewhat shorter paint than linseed oil, but linseed oil was more widely used.

Having visually analyzed many Old Master paintings over the years, I have seen plenty of indications that long oil paints were used extensively from the time of the Van Eycks up until commercially-prepared oil paints entered the picture. Long paints were not the only ones used, in my estimation, but both long and short paints were used systematically, each respectively for the purposes for which it was best suited. Of course, this varied from artist to artist, but in general, the preponderance of centuries-old paintings exhibit characteristic signs of long paint (or at least longer than today's tube oil paints) as the major component, if not the only component. I've mulled my own paints, and have painted with them and with tube paints for many years, so I am well able to recognize the visual indications of long and short paints.

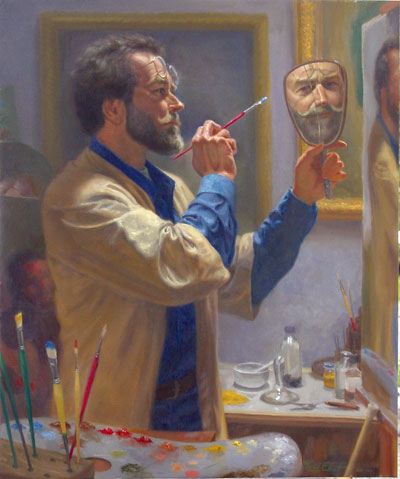

Long paints are especially suited to painting smaller pictures on smooth panels or fine-weave primed canvas with a smooth surface, using soft-hair brushes such as sable, badger, fitch or squirrel. This is essentially what the earliest practitioners of oil painting did, as an evolutionary step from the practices of egg tempera, using the same kind of gessoed panels, the same kinds of brushes, and largely the same procedures that they were already familiar with from painting in tempera. I have seen enough old paintings of artists at work with their brushes and palettes to confirm this as more than mere conjecture on my part

Self Portrait with Two Mirrors, oil on canvas mounted on panel, 36 x 30 in., 2002

Subsequently, other variations entered the picture, probably due to commissions for very large paintings, for which stretched canvas was found to be a more suitable support, for practical reasons such as transportability, etc. The texture of canvas requires larger quantities of paint to cover a given area of surface. Hog bristle brushes hold more paint, and give different kinds of brushstrokes, with softer edges, so the adoption of canvas supports was instrumental in the evolution of oil painting techniques from the practices of the early Flemish to the Grand Manner of the Venetians.

Rembrandt made good use of both long and short paints; short for his stiff impasto underpainting, facilitated in part by adding egg yolk and chalk, etc., to the underpainting white (which ingredients have been detected by scientists analyzing paint samples from his paintings), with the principal binder being uncooked linseed oil.

Some colors exhibit a natural tendency of being "long." Ultramarine blue without stabilizers is an extreme example of "longness" in oil paint. Yellow ochre mulls into a somewhat long oil paint in linseed oil and, of course, each pigment has its own unique handling characteristics, which modern manufacturers try to mitigate in the interest of uniformity. It seems highly likely to me that the Old Masters did not strive for uniform consistency or handling of their oil paints, but rather learned to exploit these individual differences to good effect.

For these reasons, I think long oil paints are valuable for artists who wish to incorporate Old Master-like effects into their work. Short paints are already available everywhere. Walnut oil paints (short) are being sold by M. Graham and Robert Doak, for example, and most other manufacturers are now using safflower oil (also an oil that makes short paint) for at least some of their oil colors. Most of the companies who are using linseed oil are still making paints short by adding too much (in my opinion) stabilizer and perhaps doing other things to give that result. So the most unique oil paint a specialty manufacturer could provide today would be one that is longer than any of the others.

Written by Virgil Elliott. Visit his web site.

The author, Virgil Elliott, at his easel.

Oil Paints Made Like Those of the Old Masters

Rublev Colours Artist Oils are unlike any other brand of oil paints today. Why are Rublev Colours different from other manufactured oil paints? One reason is that we use genuine natural and historical pigments like those used by the old masters. Most of these pigments are not found in other brands. Another reason is that we make Rublev Colours Artist Oils as they did before modern tube colors—without additives. Rublev Colours Artist Oils contain only pigment and oil. They are formulated to maintain the unique characteristics of each pigment in oil. The character found in each tube of our oil colors is unique due to the pigment inside, giving the artist new choices of texture, opacity, consistency, tone and hue. With Rublev Colours you experience the transparency of yellow ocher, the pale coolness of green earths, and the crystalline glitter of blue lazurite.